Spotlight Archives

Interviews with authors of new books on migration and mobility

April 2025 Spotlight

Farrah Mina interviews Arang Keshavarzian about the book Making Space for the Gulf Histories of Regionalism and the Middle East (Stanford University Press, 2024)

About the author

Arang Keshavarzian is an Associate Professor of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies at New York University. He is the author of Bazaar and State in Iran: The Politics of the Tehran Marketplace (Cambridge UP, 2007), Making Space for the Gulf: Histories of Regionalism and the Middle East (Stanford UP, 2014) and co-editor, with Ali Mirsepassi, of Global 1979: Geographies and Histories of the Iranian Revolution (Cambridge UP, 2021). His articles on various topics have appeared in several edited volumes as well as Politics & Society; International Journal of Middle East Studies, Geopolitics; Economy & Society; Arab Studies Journal; and International Journal of Urban and Region Research.

About the interviewer

Farrah Mina is a second-year master's student at the Hagop Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies. She is drawn to migration, urbanism, and placemaking in the UAE, with a particular interest in everyday urbanity, informal public spaces, and emergent forms of belonging. She is currently a Jack Shaheen Media Fellow at the Arab and Middle Eastern Journalists Association. Prior to pursuing a graduate degree, Farrah worked as a journalist, writing youth-centered news for Minnesotans impacted by family policing and the forces, largely race and poverty, that thrust families into traumatic encounters with child protective services.

Farrah Mina: Let's start with the title of the book—Making Space for the Gulf. Why did you choose this title, and how does it reflect your central arguments?

Arang Keshavarzian: The title originally was Making Space Out of the Gulf. This was because the larger project is thinking about how the Persian Gulf, which is a body of water and also a social space, becomes transformed into a region and an abstract space; something that can be identified on a map and treated as a unit. The editors wanted a different title, and they thought Making Space for the Gulf was more idiomatic. They're probably correct about that, but also that made sense to me. There was a logic there because Making Space for the Gulf touches on the question of how the Gulf fits into other political and spatial projects, such as empires, nation-states, the global, and the urban. The central point is to think about space in relation to other processes and places, but also to think about the production of space.

FM: You treat the Persian Gulf as a process rather than a fixed entity, and regionalism as an outcome rather than a given. What motivated you to adopt this perspective, and how does it challenge conventional understandings of the region?

AK: The central conceptual move that I'm making is to think about spaces in general, including the Persian Gulf, as a social process. As I was doing my research, I landed on this notion that we have to think about space and place as a multiplicity—not as a singular object or something that's static. An approach to space that’s more processual allows us to grapple with the reality that places mean different things to different people, depending on where they're located in social hierarchies, geographically, historically, and in relation to political power. In this formulation, the Persian Gulf is not a fixed territory that can be controlled or dominated, belonging to one nation or empire. It is invariably something that's fluid, changing, and shifting. It ultimately emphasizes that places such as the Persian Gulf are never fully enclosed. They always have permeable boundaries.

FM: What were some of the methodological challenges that you faced writing this book, and how did you navigate issues of access, archive and fieldwork?

AK: If one takes a processual approach to space, then the challenge is where does one start? What are the appropriate archives? Where are the physical locations one goes to? If I was adamant on trying to tell a transnational story of the Persian Gulf, I had to grapple with multiple locations, transnationalism, and so on and so forth; or the impossibility of a comprehensive and single history. One of the challenges I had was how to organize the multiple strands of such a story. There was almost too much to handle. There are lots of histories, people, and places that are constitutive of the Persian Gulf that are left out. But I'm hopefully offering a framework for people to think about these broader questions of the making of the Persian Gulf and its transformations over the past 100 years or so.

My earlier work was very much grounded on field research, ethnography, and interviews. Readers of the book will realize that this book operates at a broader scale. There are moments where I bring in my own personal experience, and there are certain moments that will feel like social history. My sources range from newspaper articles to colonial archives to interviews. But I did have a real methodological challenge in that I had limitations of accessing many sources I planned to examine and to travel to many countries of the Gulf. This was true of Iran where it became more difficult for me to do field research after 2009, but also when my plan of spending a long period of time in the United Arab Emirates and NYU Abu Dhabi was scuttled when I was denied entry. We need to have more frank conversations about the politics of field research in the Gulf region and the limitations it places on the stories we tell.

FM: Your book is structured by geographic scale rather than chronological order. What led you to make this choice, and how does it shape the reader's understanding of the Persian Gulf?

AK: Rather than organizing the book chronologically, which would result in a more teleological narrative, I encourage readers to ponder multiplicity and simultaneity. At the same moment it's an imperial space as well as a highly particular or local space—a national space as well as integral to economic globalization. Each of the chapters is looking at the process of the making of the Persian Gulf into a region, in relation to other spatial projects across many decades. The book's four main chapters explore the Persian Gulf through imperialism, state formation, global capitalism, and urban space. Even the conclusion is bringing the question of scale down to the human scale, where I'm trying to think about how Gulf regionalism is experienced, not by nation states or empires or capitalism, but by individuals. The result is that historical moments are narrated multiple times along different scales and the chapters circle in on each other.

FM: What surprised you most in the process of researching and writing this book, and were there moments that reshaped your thinking?

AK: At one point I discuss this moment when the British cement their hold on the Gulf region at the end of the 19th and start of the 20th centuries. Interestingly, British colonial officers talk about British power over the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf as a Monroe Doctrine for the British Empire. This was surprising to me because here is a case of British imperial thinkers and colonial officers referencing US global power. The Monroe Doctrine famously is the US political doctrine going back to the 1800s and their relationship to Latin America as a large territorial unit, in the same way that the British had come to think of the Gulf and the Northern Indian Ocean. We usually tell the story that it is the US Empire that learns imperialism from the British. But here is a clear instance where the British are actually looking to the US for a model of spatial control.

A more abstract point that I came to realize is oftentimes when we talk about transnationalism, movements, and connectivity, we resort to very naturalistic language. We talk about ‘flows,’ ‘tsunamis’ and so on and so forth. As I was doing my research, time and again, I realized that people aren't just simply moving willy nilly from one place to another. They're forced to go to certain places and blocked from going to others. So, one of the things that I learned was to think about mobility and immobility together—to think about movement in terms of channeling, rather than flows. Even if people are connected, even if people have been moving from one place to another throughout human history, it doesn't just happen on its own accord and it is deeply political.

FM: Lastly, who are you hoping will read this book, and what kind of impact do you want it to have?

AK: I hope it encourages people to think about space and places as processes, but also ultimately to force people to denaturalize geographic categories like space, region, and nation. Geography is not some sort of background condition, but something that's being shaped and fought over. It is not separate from society, but integral to it. I tried to write the book in a way that's somewhat light on jargon that can be attractive to people who don't know much about the Middle East and the Persian Gulf or are not vested in one or another discipline. I ended up cutting out a lot of more detailed parts to make the book approachable to those who may not be immersed in these histories. Hopefully, it'll be inspiring—or frustrating— to graduate students to explore the region as a key vantage point for understanding the modern world, the U.S., capitalism, gender relations, and many, many other things. If how we imagine and circulate through the Gulf shapes how we see the world, then it is a powerful lens to contemplate many issues well beyond its shores.

You can purchase the book here.

You can watch a book talk featuring Arang here.

October 2024 Spotlight

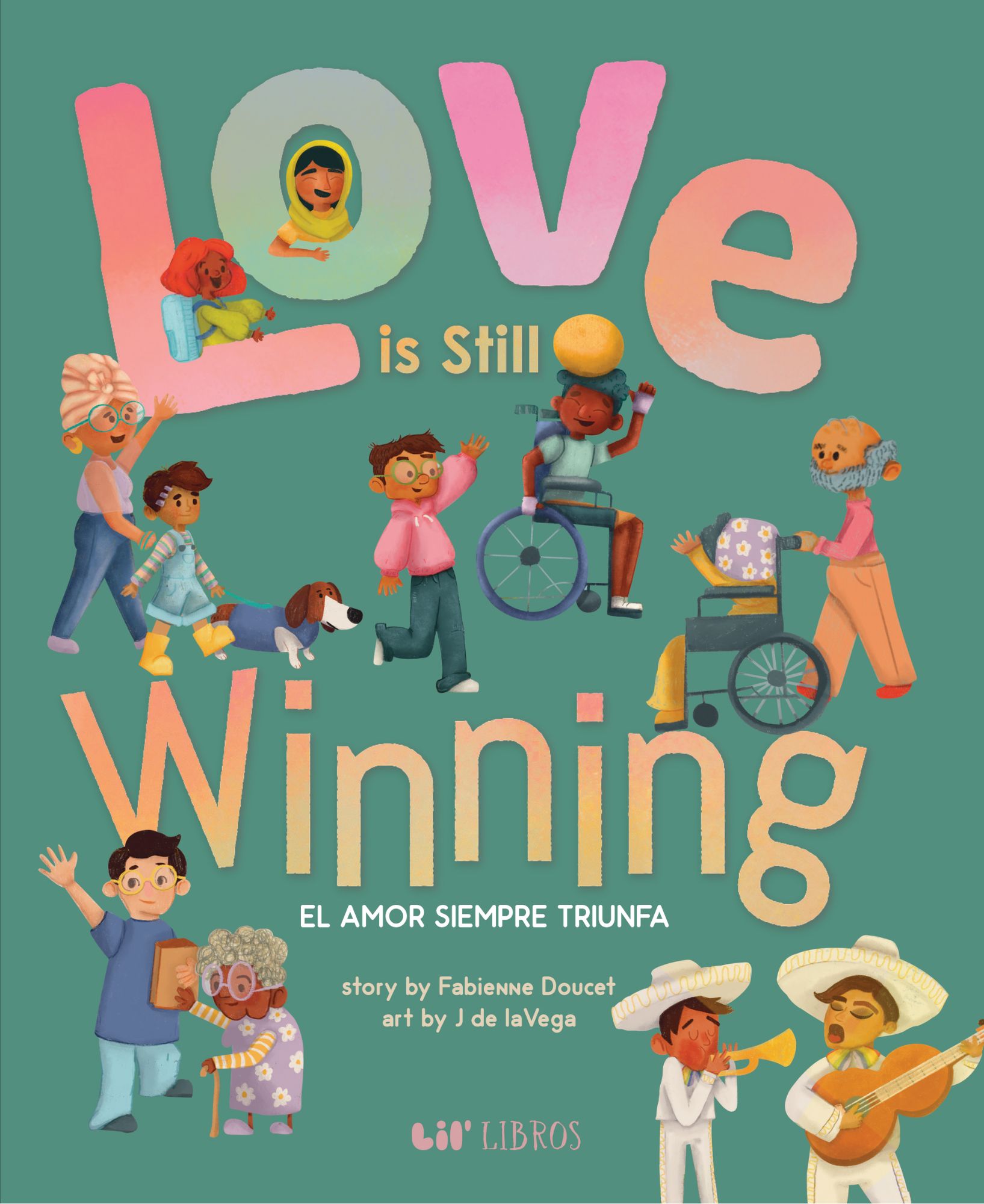

Laura Assanmal interviews Fabienne Doucet about her book El Amor Siempre Gana/Love is Still Winning (Lil’ Libros 2024)

About the author

Fabienne Doucet takes an interdisciplinary approach to examining how immigrant and U.S.-born children of color and their families navigate education in the United States. A critical ethnographer, Doucet studies how taken-for-granted beliefs, practices, and values in the U.S. educational system position linguistically, culturally, and socioeconomically diverse children and families at a disadvantage, and seeks active solutions for meeting their educational needs. Doucet has numerous scholarly publications and is author of the children’s picture book Love is Still Winning/El Amor Siempre Triunfa (Lil’ Libros Press). She has a Ph.D. in Human Development and Family Studies from UNC-Greensboro.

You can connect with the author on Instagram: @bailabomba

About the interviewer

Born and raised in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, Laura Assanmal Peláez is an urban ethnographer, community organizer, and doctoral candidate at NYU Steinhardt’s Sociology of Education Program. Her research explores how immigrant and unhoused students exercise agency in a city and school system where they encounter oppressive geographies.

Laura is currently a member of the adjunct faculty of Education Studies Program at NYU Steinhardt, an incoming adjunct instructor at NYU Gallatin School of Individualized Study, a Urban Democracy Lab Doctoral Fellow in Urban Practice, and a graduate researcher at the Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools.

In this interview, Laura Assanmal speaks with Dr. Fabienne Doucet, Executive Director of the NYU Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools and an Associate Professor of Early Childhood Education and Urban Education at the NYU Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human about her first bilingual picture book: Love is Still Winning/El Amor Siempre Triunfa.

This children’s book tells a story of a child reminding their mother about the enduring power of love and kindness in the face of prejudice, racism, and anti-migrant sentiments. The book begins with a mother overwhelmed at a news story of calls to “build a wall” in the U.S. Southern Border. Through tender images displaying a range of religions, races, ethnicities, and disabilities, Love is Still Winning/El Amor Siempre Triunfa encourages children to explore acts of love and service towards their communities. In this book, children and their families are encouraged to imagine a more embracing world in which love manifests itself in the form of giving, helping, opening doors, welcoming newcomers from other countries, sharing food, and listening. This book hopes to nurture in children a sense of compassion and care for communities that have been impacted by migration and displacement.

Laura:

I wanted to start by asking you about the origin story of Love Is Still Winning/El Amor Siempre Triunfa. I would love to know the beginning of how this book came to be.

Fabienne:

In 2015, I had written a different story that was a story about my family. I remember I was woken up in the middle of the night by this recurring sentence: My family tree grows magically. I couldn't stop hearing it in my head, and so in the middle of the night, in the dark, I wrote down whatever was in my mind. When I woke up the next morning, I told my husband: I think I wrote a children's book.

He was like, of course you did. It was the craziest thing in the world. I had never imagined that as an academic, despite my focus being Early Childhood and Childhood Development, that I was going to write for children. But as I began to think about this book, Donald Trump was running for president of the United States. During these years, the country witnessed marches protesting the murder of Black people by the police. There was a march protesting the death of Sandra Bland that my kids, my husband and I attended. What we saw at this march really stayed with me: so many families marching together.

Seeing families and children of all ages marching made me think about how, yes, there is so much mess going on right now, but at the same time, look at all of this. Look at all of this love. Look at all of these people showing up for each other. In this march, I witnessed a manifestation of love more than an emotion. What we saw was a kind of love that fought; that demanded rights. This experience prompted me to ask what else is love doing? And how are my children showing me to love? I started thinking about all the way love moves in this world. Loving is not simply a matter of saying “let's just cross our fingers and close our eyes and hope”. We have to live it every day. And so the story came to me, and it came to me as a bilingual English-Spanish story from the beginning.

Laura:

Triunfar, to “triumph”, has such a depth of meaning. It is more than winning a game or a single battle.

I noticed the book begins with the image of a worried mother sitting in a kitchen drinking coffee or tea, with tears rolling down her face as she reads the newspaper. Her child enters and asks her, curiously, “Por qué lloras Mamá?”, “Mama, why are you crying?”. What story did you imagine in that front page?

Fabienne:

It was a story about building the wall. About the building of a wall to keep immigrants out of the United States. It was a story calling immigrants “bad people”, “dirty people”, “rapists”, and the “worst that gets sent to our society”. That was the story in my mind that the mother in this book is reading. She is devastated, because I remember how I felt devastated when I heard that.

Laura:

This brings us to the question of how this book grapples with questions of migration and mobility. One of my favorite pages in this book features a yellow bus. Next to it, we see boxes of food and water, and we also see a family welcoming other families off the bus. In this part, you write about opening doors. Is this a nod to what we have been witnessing in New York City over the past few years, with asylum seekers being bused to New York City from the border?

Fabienne:

Wow. You know, at the time of writing this story, I was thinking about walls. I wanted to say: we don't build walls, we open doors. However, my illustrator must have gotten the story only a couple years ago. Maybe for her—and I can’t say for sure—that is what this piece of the story meant. In traditional publishing processes, the author typically does not choose the illustrator. The publisher chooses the illustrator, and the illustrator and the author typically don't know each other. I did not know J de la Vega before writing this book. But what I also didn't know at the time is that J and I were part of the same online group for radical moms. She shared that when she was offered the story, she found me in her group and felt good about taking on a project that felt so personal to her.

In the book, there is a character called Andy who is helping Señora Dominguez carry her groceries. That character represents J’s brother. There are beautiful Easter eggs and things that are meaningful to her in these illustrations. Now I really want to ask her the story behind the bus.

Laura:

There is a certain tenderness to all the bodies shown in this book. We see children, parents and neighbors with a range of abilities, races, names, religious garments and connotations. What was so important about the representations made in this book?

Fabienne:

It really mattered to me that every child would be able to see themselves in this book. I did not want anyone to be concerned about whether the story followed a boy or a girl, but simply a child. When thinking about soup kitchens, I specifically thought about a Sikh langar; a Sikh community kitchen that serves meals for anyone in need.

Laura:

That's beautiful. I want to go deeper into how this book ties into notions of migration and mobility. What would you say is your hope for how children who read this book go on to engage with people who are not from the United States, and specifically those who are undocumented? What is the hope?

Fabienne:

The hope is that children recognize the different ways that we, in community, love each other, support each other, and care for each other. The book centers the neighborhood as a crucial place for this understanding. In our neighborhoods, we have people who are born here. We have people who were born in other places. We have people who have been here for a very, very long time. We also have people who just arrived last week, and everyone is welcome.

We had an initial discussion about situating the book in New York City. New York is the context that J knows. The press, however, wanted this book to be able to be imagined anywhere. I lived in North Carolina for a very long time. So, this story could take place in North Carolina. It could be in Tennessee. It could be anywhere. We see apartment buildings, parks, and illustrations that reveal a somewhat urban place. I think there's something about it that feels transcendent, similar to how we thought about gender. I think this choice also speaks to movement and migration and where we settle and are situated. Our built environments contribute to, or don't contribute to, to the ways that we can connect with each other.

Laura:

You have been outspoken about the critical work that is instilling hope in children as part of our collective work towards liberation. I want to understand how you situate your book within that mission. What do you think is the role of children's literature in expanding children's sense of hope and possibility?

Fabienne:

There is this idea in children’s literature that books are both mirrors and windows. When we write stories, there is always an element of how we see ourselves but there is also an element of opening our eyes to something that we couldn’t imagine before. Children’s books are windows into the world, and they are also mirrors of ourselves, as adults. I hoped that this book provided everyone something they could recognize.

I want this book to be a window into how we can carry out this project of living together in community. I think children's literature has the power to do that. I recently spoke about this with Dean Jack Knott—who has been a big source of support—when I gave him signed copies for his grandchildren. Picture books only let us write 500-1,000 words, and because of that, we have to pay attention to an economy of words to convey so much in such little space. That is what is so powerful to me about picture books. You will walk after a few minutes having discovered something new, something that made you laugh, or reflect.

Laura:

We should all be reading children's literature.

Fabienne:

We really should. It’s art. Through it we can access ways of playing with language, different forms of creativity and connection.

Laura:

I have a last question. One of the things that I thought about while reading the book is about how bell hooks in all about love calls upon us to think about love not as a noun, but as a verb. And there is so much in your book that speaks to this idea of love as a verb in the form of giving, helping, including opening doors, listening. So what influences helped you shape your ideas of love and its centrality to this book?

Fabienne:

I love this question. It makes me want to cry. I devoured bell hooks’ book. I was in graduate school at the time when she wrote it, and she came to my campus in North Carolina. I got to actually ask her questions about all about love. It was transformative.

I was raised by my great aunt and uncle. My mother and father divorced when I was really young. I was born in Spain, but my mother left when I was maybe a couple of months old and moved to the US. I lived with her sister for a while, and then was sent to Haiti to be raised by my aunt and uncle. She was in the US, divorced, without knowing the country and not comfortable with the idea of dropping me off at a daycare. Her aunt, my great aunt who raised me, had told her: If you need help with your baby, you can send her to me. That offer was the greatest gift that she could have possibly given me.

My aunt and uncle, who I dedicated the book to, Maman Titine and Papa Fito, are, even though they have moved on from this world, the most loving people I have ever known. They represent love in this way. They give love in this way. They used to talk about Amour Soleil, which means “sun love”. They would say that romantic love is nice, but what you want is a love that shines bright like the sun and that shines forever. A kind of love that is not fleeting. It’s the sun. They taught me about love. They taught me, as a privileged child living in a very poor country, about respecting people who did not have the resources that we had. They taught me about the importance of being generous. They taught me that the reason I was born into this family, and into privilege, was an accident. My circumstances said nothing about me, and the lack of privilege said nothing about the person across the street. They taught me a love that is very active, outward, and service oriented. This love extends to the chosen people that I bring into the family. I think about those lessons of love, including my mom making a huge sacrifice. These people, who already had kids of their own, took another child in for 10 years. I was raised in a cocoon of love, feeling cherished and feeling valued. You can't really help but delight over it.

Laura:

Thank you. That's so beautiful.

Fabienne:

I'm just so lucky. It’s so random. I'm so lucky because it didn't have to be this way. Because of that, I don't have the choice but to keep on ensuring that other people experience this level of acceptance and unconditional love.

You can purchase the book here.

November 2024 Spotlight

Andrew Gerstenberger interviews Kevin Kenny about the book The Problem of Immigration in a Slaveholding Republic: Policing Mobility in the Nineteenth-Century United States (Oxford University Press 2023)

About the author

Kevin Kenny is Glucksman Professor of History at New York University. His books include Making Sense of the Molly Maguires (1998; 25th anniversary edition, 2023), The American Irish: A History (2000), Peaceable Kingdom Lost: The Paxton Boys and the Destruction of William Penn’s Holy Experiment (2009), Diaspora: A Very Short Introduction (2013), and The Problem of Immigration in a Slaveholding Republic: Policing Mobility in the Nineteenth-Century United States (2023). A Distinguished Lecturer of the Organization of American Historians, Professor Kenny served as President of the Immigration and Ethnic History Society from 2021 to 2024.

About the interviewer

Andrew Gerstenberger is a fifth-year doctoral candidate in the joint program in History and Hebrew and Judaic Studies at NYU. His research focuses on transnational migration, with an emphasis on German- and Yiddish-speaking migrants in the nineteenth-century United States. His dissertation examines Jewish immigrants' varied responses to American practices of enslavement, and unpacks the moral language these migrants used to justify their individual activities ranging from abolitionism to large-scale enslaving.

Andrew Gerstenberger:

This book is about the legal ramifications of the confluence of mass migration and enslavement in the nineteenth-century United States. What led you to pair these two seemingly disparate subjects?

Kevin Kenny:

My research and teaching before this book focused on immigrants seeking to make a better life for themselves and their families and sometimes engaging in social or political protest. I had never really addressed the fundamental question: Who claimed authority over immigration and on what grounds? In the United States today, the federal government controls immigration by deciding who to admit, exclude, or remove. Yet in the century after the American Revolution, Congress played only a very limited role in regulating immigration. The states patrolled their borders and set their own rules for community membership. In the Northeast, they imposed taxes and bonds on foreign paupers. In the Old Northwest (today’s Midwest), they used the same methods to exclude and monitor free black people. Southern states policed the movement of African Americans, both free and enslaved, and passed laws imprisoning black sailors visiting from other states or abroad. These measures rested on the states’ sovereign power to regulate their internal affairs. Defenders of slavery supported fugitive slave laws but resisted any other form of federal authority over mobility across and within their borders. If Congress had the power to control immigrant admissions, they feared, it could also control the movement of free black people and perhaps even the interstate slave trade. All of these forms of population movement were closely interrelated. Immigration, in short, presented a political and constitutional problem in a slaveholding republic. My book explains the origins, significance, and resolution of this problem.

Andrew:

What is the book’s central argument? What do you most hope your readers will come away from this book knowing?

Kevin:

My argument is that the existence, abolition, and legacies of slavery, more than any other issue, shaped American immigration policy as that policy moved from the local to the national level over the course of the nineteenth century in the context of westward imperial expansion. A national immigration policy did not begin to emerge until the 1870s, and the timing—during the era of the Civil War and Reconstruction—was no coincidence. The constitutional battle over immigration authority in the nineteenth century pitted federal commerce power against local police power. Which level of government had authority? Throughout the antebellum era, the Supreme Court danced around this question rather than confronting it squarely because any decision concerning immigration affected the institution of slavery, and especially the movement of free black people. If Congress had power over immigrant admissions under the commerce clause, how far would that power extend when it came to other forms of mobility? If the courts invalidated the right of Massachusetts to impose taxes or bonds on foreign paupers, what would become of similar laws in South Carolina punishing free black seamen, laws in southern states mandating the expulsion of freed slaves, or laws in both the North and the South excluding free black people? Only when the Civil War and abolition removed the political and constitutional obstacles did a national immigration policy emerge. Any understanding of this period must examine European and Asian immigration in the same historical context as African American and Native American history. Connecting these histories, which are usually told separately, reveals the foundations of present-day border control, incarceration, and deportation, as well as the ongoing tension between state and federal sovereignty in immigration policy.

Andrew:

In your previous scholarly output, you have tended to place individual migrants and their collective activities at the center of your narrative. In this book, however, you chose a top-down approach that focuses on jurisprudence and legal discourse. What led you to this decision? Did you encounter any difficulties or discover anything surprising while conducting your research or seeing the book to print?

Kevin:

Most of my previous writing took the form of history “from the bottom up.” In this book, by contrast, I adopt a “top-down” approach because of the nature of the question I am trying to answer: Who claimed authority to regulate mobility, and on what grounds? In examining the ideas, laws, and policies that were used to justify control over immigrants and black people, I am interested in what judicial opinions and decisions, legislative debates, statutes, and other official documents reveal about the logic of sovereignty and race in the nineteenth century. As a historian, I approach sovereignty as a contested claim to authority rather than a form of power whose meaning can be determined a priori. Sovereignty in this sense cannot be grasped in the abstract, only in its particular and evolving contexts. Claims to authority over immigration were always contingent and dynamic, part of an ongoing political and constitutional argument about who had the right to control borders, mobility, political allegiance, and community membership in the age of slavery and emancipation.

And yes, there were plenty of difficulties and surprises along the way. Trained in social history, I embarked on legal and constitutional analysis with some trepidation and considerable excitement. When I encountered new concepts and technical terms in my research—police power, commerce power, diversity jurisdiction—I moved outward from the primary sources to the secondary literature to find out more. Not having taken courses in constitutional law, my method was inductive, learning by doing. This process was intellectually exciting, and in the book I try to convey to the reader my excitement in answering questions I did not even know existed when I set out to write the book.

The biggest surprise in this story, for non-specialists at least, is that the Constitution provides no guidance on immigration policy. It says nothing about the admission, exclusion, or expulsion of foreigners. Its sole provision directly concerning immigration has to do with the naturalization of foreigners after they arrive—a policy that was long restricted to “free white” people. Another big surprise, for many of my students, is that Asian immigrants remained barred from naturalization until the 1940s and 1950s—even though their US-born children automatically became citizens at birth under the Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868.

Andrew:

How do your findings contribute to or alter contemporary conversations, both in the academy and beyond, surrounding mobility and migration?

Kevin:

As a historian of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, I usually don’t conclude my books with extended reflections about the present. Doing so can seem forced, with the author telling the reader the true moral of the story, explaining what the book is really about. In this case, however, an epilogue taking the story up to our contemporary movement emerged organically from the argument. The book is about immigration federalism, a question that remains vitally relevant today.

Since the late nineteenth century, as I explain in the book, the federal government has controlled immigration in the sense of the admitting, excluding, or deporting foreigners. In the Chinese Exclusion Case (1889, the Supreme defined power over national borders as inherent in the sovereignty of the United States and assigned this power to Congress and the executive, the two “political” branches of the federal government, with minimal interference by the courts. In Trump v. Hawaii (2018), the Court invoked the Chinese Exclusion Case in upholding Trump’s so-called Muslim travel ban. Recently, however, Texas and other states have challenged federal authority over immigration by seeking to control national borders directly, a question that remains tied up in the courts as we speak.

The tensions within immigration federalism today have their origins in the period I examine in my book. Although the national government controls US borders, states, counties, and cities continue to regulate the lives of immigrants, using their police power, after they have entered the country. State-level laws often monitor and punish immigrants, especially the undocumented, by restricting access to public benefits, education, employment, and property, and by cooperating with federal law enforcement. Some states and cities, however, pass pro-immigrant laws and provide sanctuary against federal surveillance, complementing grassroots efforts by faith-based organizations and other activists. States and cities cannot defy federal immigration law—but neither can the federal government order them to participate in enforcing that law. There is parallel here with the antebellum era, when Southern states demanded stronger fugitive slave laws at the federal level and Southern states passed personal liberty laws providing refuge for fugitives and free black people in danger of being kidnapped into slavery. Local sovereignty, understood in this way, is not simply a matter of autonomy from the federal government. It can also entail an obligation to protect all people, of every background, to enhance the general welfare. Rights can be protected even more effectively if defined nationally and guaranteed by the federal government, but in the contemporary context cities, counties, and states have a vitally important role to play.

Andrew:

Are there any areas of related research you didn’t have space to examine in this book that future scholars might undertake?

Kevin:

Writing this book has made me think more about the multiple ways in which US immigration policy intersected with Native American history. This theme is important in my book, but it remains secondary to the main theme of slavery. In my current research, I am exploring the intersection of immigration history with Native American history in the period from 1789 to 1924, focusing on questions concerning land, citizenship, and sovereignty. This project addresses, to coin a phrase, the problem of immigration in a settler colonial nation.

You can purchase the book here.

December 2024 Spotlight

Haneul Lee interviews Ethiraj Dattatreyan about the book Digital Unsettling: Decoloniality and Dispossession in the Age of Social Media (co-authored with Sahana Udupa, NYU 2023).

About the author

Ethiraj Gabriel Dattatreyan is an assistant professor of Anthropology, core faculty in the culture media program, and affiliated faculty in the department of music at NYU. For the last decade he has utilized collaborative, multimodal, and speculative ethnographic approaches to research how media consumption, production, and circulation shape understandings of migration, gender, race, and urban space in diasporic and postcolonial contexts. He is the author of two books, the Globally Familiar: Digital hip hop, masculinity and urban space in Delhi (Duke University Press 2020), and Digital Unsettling: Decoloniality and Dispossession in the Age of Social Media (co-authored with Sahana Udupa, NYU 2023).

About the interviewer

Haneul Lee is a documentary filmmaker and a PhD candidate of the Martin Scorsese Department of Cinema Studies. Her dissertation, Platforms of Care: The Global Life of Grassroots Media, explores alternative video production and circulation across platforms for protesters, female migrant care workers, and queer fan-video makers. A portion of her dissertation chapter is included in an anthology, Made in ASIA/AMERICA, published by Duke University Press. Including a short film A Letter to the Letter (2024), her films have been invited to film festivals.

Haneul Lee:

Your book, Digital Unsettling, speaks of what “the digital” implies in the age of digital media by exploring the complexities and contradictions inherent in digital media that we engage in. Can you tell us the story of how this book came to be?

Ethiraj Gabriel Dattatreyan:

Digital Unsettling came out of a series of conversations that I had with my co-writer, Sahana Udupa, who is a professor at Ludwig-Maximilians University (LMU). We first met in 2011 at the University of Pennsylvania where Sahana was doing a postdoc and I was finishing up my PhD. We’ve been in conversation since. In a chat we had back in 2018, she and I discussed how recent theories of the digital left much to be desired as they posited an ahistorical framework for engaging with social media. About a year after this chat, Sahana hosted a workshop at LMU on decolonizing media research. I attended and together we, along with several other scholars, tried to think through what decoloniality as a historical backdrop, a concept, a method, and a political orientation, offered media anthropology and its scholarship on the digital. Soon after the workshop, Sahana invited me to write this book with her.

Haneul:

You and Prof. Udupa offer “decolonial sensibility” as an analytical framework and tool. However, I think that the term decolonial is often used metaphorically or symbolically. Can you tell us about your approach to the term “decolonial”?

Ethiraj:

Decoloniality means different things to different people, in part depending on location. For example, in North America, decoloniality is very much tied to native struggles and offers a powerful argument and political impetus for native sovereignty. Land back! In the Latin American tradition, decoloniality signals an attention to the enduring ‘coloniality of power’ that continues to shape economic, social, and cultural relations. Our challenge was to figure out how our long-term field engagements across various locations – the US, the UK, Germany, India, and South Africa - gave us particular insights into how decoloniality is being articulated in social media spaces in ways that draw from these and other overlapping yet distinct traditions and what our own positions/claims to the concept were. In the book we approached decoloniality in three key ways. First, as a subject of study that appears in online spaces linked to offline social movements; second, as an analytical strategy to push against ahistorical studies of digital media; third, as an ethical and political commitment to developing, cultivating, and sustaining a decolonial sensibility, what we describe in the book as a commitment to working through the ruptures and tensions between multiple and distinct struggles for freedom, equity, and justice.

Haneul:

The chapter on campus as a site of struggle echoes the recently emerging student activism in the US and beyond to build solidarity for Palestine or other political issues. What can we learn about the colonial structure of those social and political conflicts beyond here and now?

Ethiraj:

The campus chapter draws on lessons learned during the South African and UK struggles for racial and economic justice, focusing on how students from across geographic locations utilize social media to directly and indirectly learn from one and other to directly challenge colonial continuities. Learning, we show, is affectively charged and affect, as it is channeled through social media, reveals the resonance of shared colonial histories across contexts. In the chapter we also consider the ways the university works to defuse university social movements by coopting and taming its goals. We foreground the asymmetries of position in university struggles and show how students’ link various issues together – campus police brutality, high tuition fees, racist curricula, and so on – as part and parcel of a colonial legacy and do so in ways that recognize cross-border struggles. What we didn’t discuss in the book, which has presented itself forcefully in the last year, are the ways outside groups – like Canary Mission in the US, for example - seek to disrupt campus based social movements through various tactics of intimidation that rely on digital surveillance, online doxing, amongst other tactics. As has become very apparent in the last year, these outside groups, when coupled with an institutional logic that reinforces an ahistorical position when it comes to, for instance, speech, puts already vulnerable students, academics, and workers who are struggling for a more just campus and world, at even greater risk.

Haneul:

Yes, in that way, the campus chapter would have offered a more expanded view on student activism in the age of social media.

Ethiraj:

Agreed. This reveals, perhaps, one of the limits of ethnography. We were grounding our arguments in relation to what I was witnessing in real time in the UK circa 2018 – when I taught in London. I utilized what I participated in and observed to draw connections to other campus movements. Our goal was to show how student generated unsettling moved through the digital across borders and what the responses at the institutional level were to demands for redress. We didn't want to start free floating with our analysis. The danger is, of course, that in not thinking with other contexts, certain modes of unsettling are left out of the frame.

Haneul:

Thinking of decolonial sensibility that generates affective capital beyond a national border, I wonder how this book could contribute to the larger discussions of migration and mobility?

Ethiraj:

The migration and mobility literatures tend to focus on the movement of people across naturalized borders and key questions focus on the mobility/immobility of people in relation to nation-states and their legal apparatus and, in some cases, the post-war international order that produces these relationships. Our book focuses on a different kind of mobility, one that attends to the cross-border potentials of media circulation in the digital moment and the kinds of unsettlings of taken for granted understandings of citizenship, belonging, etc. these text, image, and video circulations generate. To return to the campus chapter, I was really intrigued by the cross-border resonance that images of the Rhodes statue being pulled down in South Africa generated in their movements. In the context of Goldsmiths, where I taught, second and third generation hyphenated British college students– those whose parents or grandparents migrated to the UK in the postwar period from the Caribbean, South Asia, the Levant, and West Africa in search of jobs and worked to rebuild the country after the devastations of war – took up this image as a call to cross-border call to action. An attention to contemporary circulations of media in relation to previous moments of colonial and imperial era migration, forced and otherwise, opens up interesting ways to think about migration and mobility on multiple scales and pushes back on the nation-state as an organizing principle for research.

You can purchase the book here or access it here.

February 2025 Spotlight

Gina Caputo interviews Cristina Vatulescu about the book Reading the Archival Revolution Declassified Stories and Their Challenges (Stanford University Press, 2024)

About the author

Cristina Vatulescu is Associate Professor of Comparative Literature at New York University. Her first book, Police Aesthetics: Literature, Film and The Secret Police (Stanford UP, 2010) won the Heldt Prize and the Choice Outstanding Academic Title Award. She is also the co-editor of The Svetlana Boym Reader (Bloomsbury, 2018), and a Perspectives on Europe special issue on Secrecy (2014). Her most recent book is Reading the Archival Revolution: Declassified Stories and Their Challenges (Stanford UP, 2024), and she has started work on a new book project entitled Arts of Attention: A Literary Seed Bank.

About the interviewer

Gina Caputo is a second-year Master's student in NYU's XE: Experimental Humanities and Social Engagement program. She is an interdisciplinary (im)migration researcher who is concerned with the essential dignity, right to self-determination, and mobility of people on the move. Her research focuses on the U.S. and Italy, with an emphasis on how law and bureaucracy impact people's lives. Outside the classroom, Gina works as an immigration paralegal and organizes with Yonkers Sanctuary Movement. She holds a Bachelor's degree from Sarah Lawrence College. You can find more about Gina's work at linktr.ee/ginacaputo.

Gina Caputo: The book is as much a meditation on reading as it is an exploration of declassified Soviet secret police archives. In the archives, you encounter rumors, censorship, literary fiction, informant reports, interrogation transcripts, and bureaucratic marginalia; photographs, film stills, even an x-ray. You structure each chapter around a different "reading challenge": silences, mediums, fictions, and data. How do you deal with these challenges?

Cristina Vatulescu: Many archives are multimedia. In some ways the secret police archives are hybrid or multimedia on steroids, because the preservation requirements that we usually have in archives that keep photographs away from text, or x-rays, etc., here are overwritten by forensic imperatives that require keeping all these materials together. One of my case studies is the secret police investigation file of a 1959 Romanian bank heist. It contains all sorts of text: wiretapping transcripts, investigation records, and confiscated novels. It also contains family photographs, identity photographs, state photographs, and a reenactment film that the secret police made, in which they cast the arrested suspects themselves.

I argue that the secret police archives make meaning and wield power not within one medium, and not even within neatly separated multimedia, but through intermedia: the crafted collusion of different mediums. A photograph in a secret police file doesn't make its point unless it has a caption, right? It could be someone's lover that you see in a photograph, and for the police it could be a criminal. This connection between word and image is really important, posing a real challenge to our specialized, very disciplinarily specific methodologies. I take inspiration from contemporary artists and filmmakers in Eastern Europe to devise technologies with which we can reclaim this archival hybridity for our own reading purposes.

GC: Your book investigates archives in various locations (Romania, Poland, France, the former Soviet Union) and languages. What have you learned in this process that might help guide future migration researchers?

CV: Important migration documents can be found in these and other hostile archives. There have been many forced mass migrations, deportations, and relocations that are most extensively documented from the point of view of the state/those carrying them out.

In the book, I look at the files that the Romanian Securitate (secret police) dedicated to the German minority and their mass exodus from Romania to Germany in the 1980s. This was a minority that had been there for over a thousand years. It's probably in the secret police documents that we have the most comprehensive statistics, as well as really granular information about how people made decisions about leaving their home. In wiretapping transcripts, you have people's conversations around the kitchen table about what made them decide to emigrate. I look at the 46-volume "problem file" on the Germany minority and files of individual writers who went through this emigration process.

In dealing with files located in archives in different parts of the country, or in different countries, and multilingual files, collaboration is key. One of my chapters is co-authored with Anna Krakus, who did the research in the Polish IPN archives. For the chapter on Herta Müller and the German minority, I got help from my husband and his family.

Lastly, my book's main grounding in declassified Eastern European archives shows that a transnational peripheral perspective on Soviet and Russian centers of power yields not just access, in cases where Russian archives are now often closed, but also fresh insights and the potential to dislocate the long-unquestioned Russocentrism at the heart of Russian, Eastern European, and even Eurasian studies.

GC: Visiting the secret police archives, you encounter prison interrogation transcripts, informant reports, and surveillance documentation on people like Herta Müller, Michel Foucault, and Monica Sevianu. How do you prepare yourself for these visits?

CV: One of the most obvious ways to prepare is to learn the jargon and the history of these archives and these institutions so that you can decipher their specialized language. Secret police archives have different kinds of files: personal files focused on one individual; agent files for informers; and "problem files" covering specific questions. Some of the Romanian Securitate's problem files concerned minorities, literary circles, and Radio Free Europe.

You can't ever stop at the deciphering stage. It's easy to become complicit in the secret police's ways of reading and representing people. Their language tends to bleed into our language, which carries really important consequences as to how you look at people, for example, how you could look at a minority as a "problem."

We all bring strategies that we've honed through our lifetimes to the archive room. I bring everything I've learned in literary studies to the table: my early training in deconstructive reading is really important to deconstruct the power of these documents. There's also close reading, distant reading… different documents and voices require very different approaches. When you read an interrogation transcript, you have to read in a paranoid, hypercritical way of the secret police, and you have to try to do some reparative reading for the sake of people represented there, yourself, and your readers. So it's really bringing everything you've got to the archive.

Watching people coming to the archives to read documents related to their families, I've noticed certain gestures. The way that people sometimes bend down to look at a document reminds me of the way that people bend down at graves.

GC: Can you speak about the sensory aspects of the archives?

CV: When I take my students to the archives, one of the first things they note is what a powerful sensory experience it is to encounter the bodily traces of people who may be long gone: their handwriting, their fingerprints, their photographs, the way that they folded a paper or an envelope… People talk about getting goosebumps in the archive.

Oftentimes as we become professionalized, we either become more numb to this, or we put up a facade, or a shield, and retreat into a cone of objectivity, which I think is quite fictional. Archives remind us of something that digital and even print readings make immaterial and invisible: the embodied encounter between traces of others and our own embodied, perceiving body that reading is. Secret police archives do that at a very intense level. There is a long history and tendency of overlooking the body in the archive, the archived body, the perceiving body. I think there is a real ethical, political potential in admitting and even tapping into this embodied encounter that reading can be. I developed a practice of embodied polyphonic reading, which works against this illusion of a transparent, unaffectable, objective reader.

GC: Current fiction seems preoccupied with archives, which hide earth-shattering revelations or hold back supernatural forces. Your book shows that secret police archives hold fewer secrets than we might imagine. You examine the Romanian Securitate archive for documents regarding author Herta Müller, who believed that her personal file had been partly destroyed. You conclude that her file seems incomplete because agents routinely overlooked women and left many acts of violence, torture, and harassment unrecorded. What do you make of the distance between what we imagine these archives hold and their actual contents?

CV: The two chapters about silences are also really about expectations. I find something that Ann Stoler also finds in colonial archives: these archives and the powers that created them were much less omniscient, omnipotent, and omnipresent, than people have imagined. They're often full of hesitations, muttering and stuttering, and agents' frustration. That's interesting. At the same time, how does this help the people who lived their lives thinking that they were followed by this omniscient regime, and who made decisions on what to tell their families based on the fact that there might be a wiretapping device in their home?

People who were in the secret police's power tend to over-estimate that power, even Herta Müller, whose novels are some of the most amazingly nuanced representations of living under a police state. When it came to her own file, she over-estimated, and I think she also indulged the kind of terrified fantasies that people have about their own files. The same thing with Foucault: he's the father of archive theory, and his understandings of the archive are of course in his theoretical texts extremely sophisticated. When it came to his expectations of what would be in his Polish secret police files, or how he would be followed, he's as full of clichés and as simplistically terrified as the next guy.

GC: Who do you hope will read this book, and what kind of impact would you like it to have?

CV: People who work in hostile archives, whether in Eastern Europe or in colonial contexts, are my direct audience. More broadly, this book is about the challenges and potentials of reading, at a time when the experience of reading is changing so drastically. Ultimately, I hope that anyone interested in our present reading crisis might be interested in this book. It's a book about reading documents and fictions and each other, conceiving of these three as a continuum rather than distinct realms.

You can purchase the book here.